Share This

Cookbooks fill our kitchen shelves. Some are pristine, with pages that have barely been turned. Some are a bit dog-eared. And then there’s Deborah Madison’s Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone, which bears witness to splatters and dribbles from all the many meals we’ve cooked from its pages. We love this book and we love Deborah’s food sense. A skilled chef and a writer with a beautiful voice, Deborah is a longtime friend of Oldways. She attended many of our overseas symposiums, was a speaker at the early traditional diet conferences in the US, and was involved in the early days of the Chef’s Collaborative.

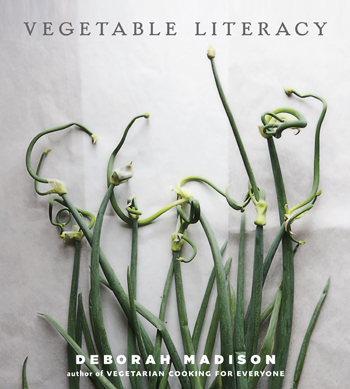

When we learned that she has come out with a new book, Vegetable Literacy, we couldn’t wait to read it and then catch up with her to chat about it.

OLDWAYS: Vegetable Literacy focuses on 12 plant families and the relationships of their members to one another. There’s such a lovely earthiness to many of your observations, and it’s clear that you have a profound connection to your garden. What lessons do you think urban dwellers with no plot to tend can take away from this book?

DM: Although it was informed by my garden, Vegetable Literacy isn’t really about gardening. Rather, it’s about learning to see and making sense of what we’re looking at, which is what my garden taught me. But I believe that the book will provide some “a-ha’” moments for urban readers when they go to their farmers market, visit a botanical garden, stroll through a neighborhood where there are front yard gardens, or enter a flower shop or even a supermarket. There are many places to view plants even if you can’t grow them yourself.

The farmers market has great possibilities for connecting to some of what I write about. One, you’ll see many more varieties of plants there, and parts of the plants we don’t see elsewhere. One of our farmers sells broccoli leaves, and cooks up samples—a case for “using the whole plant.” Occasionally one will bring in an entire mature leek just so that people see how enormous the whole plant is and what a small part of it we actually eat, or another will offer an heirloom squash that’s covered with warts or another that looks like a giant peanut and tastes absolutely divine—a case of seeing a vegetable that’s related to something common we already know, like a butternut squash. If you understand that the vitamins and other nutrients are in the radish leaves, not the roots, and that you can use them to make Radish Leaf Soup or include them in salads, you might start looking at common bunched radishes in a new way. Or you might recognize a shiso leaf that you’ve seen at a sushi bar that some enterprising farmer is selling. As long as we eat and shop for food, there’s the chance that we can open our eyes and our senses to see it more clearly.

Most of all, what I experienced in writing Vegetable Literacy, which I hope is contagious, is the sense of joy that comes with learning a few things about the world we move through everyday and becoming more intimate with it.

OLDWAYS: Tell us a little bit about the genesis of VL. Do you think it took years of working with vegetables for you to truly know these foods and sense their connections or does it reflect a new way of seeing?

DM: I think both are involved, but there is something about being up close to growing things to enable one to see differently. That’s the short answer.

My father was a botanist and even though I didn’t start to garden until I was 35, there’s something about having a parent pointing out plants and muttering Latin names that somehow gets into you. And I’ve been working with vegetables for so long that I was (and I suspect anyone would be) bound to see relationships in forms and flavors eventually. But having a garden, planting seeds, watching plants grow, harvesting, sharing, cooking and all of that, brought those forms and flavors into focus in a way I didn’t expect, from the seed I planted to the seed I saved.

The immediate genesis of the book started when I had let some carrots winter over and the next year when they flowered, I couldn’t help but notice not only how pretty they were, but that they resembled a lot of other flowers I knew—parsley, fennel, Queen Anne’s lace, tiny chervil, larger dill and lovage and giant angelica. It turns out that these are all member of the same family. Through cooking I already knew that carrots, another family member, were good with dill, parsley, lovage, fennel seeds, cilantro, chervil and other umbellifer herbs. And that’s when I started to look around and wonder how other plants were related botanically and in the kitchen.

OLDWAYS: We’ve always been impressed by the wonderful way you combine foods and flavors, and were so happy to see that you list good companion foods for each vegetable you include. For the novice cook who isn’t very secure in the kitchen, what do you think are the best ways to start experimenting?

DM: Well, one way is to just plunge in, of course. But there are two guides that I use. One is that foods in season together taste good together. (That means local foods, of course, not the world wide season of the supermarket.) The other maxim I use is that foods that are related are probably somewhat interchangeable, with subtle differences. Cooking times might differ among chard, spinach, beet greens and lamb’s quarters (all goosefoots) but the flavor is pretty much the same. Likewise, in the cabbage family kale, arugula, radish greens, turnip greens and kohlrabi leaves have a similar shape and also flavor, though some are milder than others, some are tougher, others are tender. But if you have kohlrabi with its leaves on, you might just give cooking them a try. And you might use some of the seasonings that you know are already good with kale or broccoli. Chances are you won’t go wrong.

So if you experiment within seasons and plant families you’re probably going to discover some new foods, many that were there all along but just not used. You will end up finding new cooking times, noticing how much one green collapses and how its relative holds more volume, that sort of thing, but plunge ahead and you’ll be sure to broaden your world of food and flavor.

OLDWAYS: If you think back to the time when you wrote your first cookbook, what are some of the biggest changes you see today in the world of vegetable cookery?

DM: It’s gotten better for everyone.

We finally know that vegetables aren’t just for vegetarians. Chefs and cooks of all stripes have discovered how good they are, and how beautiful, too. And now they have all these official stamps of approval from the dietitians as well, which has helped to make them more attractive.

We have a vastly wider selection of vegetables to work with than we did 30 years ago, thanks to groups like Seed Savers Exchange who really started the movement to bring the heirlooms back into view. And Oldways did a lot to open our eyes on those early trips that exposed chefs and food writers to some amazing plant foods, who then came home and wrote about them or cooked them in their restaurants.

With the growth of farmers markets and better (organic) farming methods more people are able to eat vegetables at their peak of flavor rather than vegetables that are weeks (or months!) old —truly fresh, not just unfrozen, and that’s been significant, I believe, because really fresh vegetables are so amazing.

The farm-to-table and seasonal-local eating thrust of the past decade or two have exposed people to unfamiliar vegetable varieties as well as other foods, well-grown and picked and cooked at the peak of flavor.

We have more to work with and a much more free and experimental approach to vegetables and their place on the menu. And being vegetarian isn’t such a life-style issue any more. It can be a meal, a day, a week, or a lifetime. What a relief! That opens doors to plant foods considerably.

OLDWAYS: You mention coconut butter in a number of your recipes. What are some of your other favorite ingredients that might be new to your readers?

DM: Smoked paprika. Smoked salt. Shishito peppers. Whole head lettuces again plus some gorgeous varieties. Some amazing heirloom winter squash are making a comeback. The many fine olive oils that are now produced in the US, plus some really good cornmeals made from corn varieties nearly forgotten, and flours made from old variety wheats. Freekeh (which I first had on an Oldways symposium) is now being produced in Oregon by Anthony Boutard and by other farmers. Native wild rice and many of the other vegetable, fruit and grain varieties that have been focused on by Slow Foods’ Ark of Taste are increasingly available. Then there are herbs like lovage and rau ram, or the buds of coriander seed while they’re still green (one advantage of having a garden). We have all these “new” varieties of old beans that we never had before, as well as tomatoes and other foods. All in all, there’s quite a cornucopia to draw from today. Even eggs are good again. Sometimes you have to do some extra work to find it, but it’s there for sure.

OLDWAYS: Your book is rich in wonderful tips. We loved your trick for cooking sweet potatoes in a pressure cooker. Can you tell our readers how to do this?

DM: Here are the instructions from the book: “Pour water to a depth of 1 ½ inches into the pressure cooker, then add a steaming basket. Scrub the sweet potatoes, and put them in the basket. Lock the lid in place, bring the cooker to high pressure, and leave for 20 minutes if the sweet potatoes are large or 15 minutes if they are very small, then release the pressure quickly. Check to make sure that they are completely soft by piercing them with a knife. If not, return them to high pressure for another 5 minutes, then check again. To speed up the cooking, cut the tubers into smaller pieces before putting them in the cooker.”

OLDWAYS: We’d love to include a recipe from the book. It’s almost impossible to pick just one, but may we have your permission to share the ivory carrot soup?

DM: Of course!

Ivory Carrot Soup with a Fine Dice of Orange Carrots

Serves 4-6

What happens if you make a carrot soup with just white carrots? Although the carrot flavor is fully there, garnishing the soup with carrot greens and finely diced orange and yellow carrots locks the flavor in more firmly. This is an extremely simple soup, intentionally so to underscore the purity and color and flavor. Try making it with pale yellow carrots, too.

Ingredients:

1 tablespoon butter

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 onion, thinly sliced

1 pound white carrots, scrubbed and thinly sliced

1 tablespoon raw white rice

Sea salt

½ teaspoon sugar

1 thyme sprig

4 cups water or light chicken stock

Few tablespoons finely diced orange carrots and/or other colored carrots

Freshly ground pepper

About 1 tablespoon of minced fine green carrot tops

Directions:

Warm the butter and oil in a soup pot and add the onions, white carrots, rice, 1 teaspoon salt, and the sugar and thyme. Cook over medium heat for several minutes, turning everything occasionally. Add 1 cup of the water, cover, turn down the heat, and cook while you heat the remaining 3 cups water. When the water is hot, add it to the pot, cover, and simmer until the vegetables are tender, about 20 minutes.

While the soup is cooking, cook the diced carrots in salted boiling water for about 3 minutes and then drain. When ready, let cool slightly, then remove and discard the thyme sprig. Puree the soup in a blender. Taste for salt and season with the pepper. Reheat if it has cooled.

Ladle the soup into bowls, scatter the diced carrots and carrot tops over each serving and serve.

“Reprinted with permission from Vegetable Literacy by Deborah Madison, copyright © 2013. Published by Ten Speed Press, a division of Random House, Inc.”

Add a Comment