Share This

Earlier this year I had the great pleasure of attending an event at the Culinary Institute of America at Greystone, in California’s Napa Valley. It was the first time I’d been to Greystone, and it lived up to all the hype I’d heard over the years.

The event was the annual scientific and media conference organized by The Peanut Institute. The speakers included scientists with the latest research on the healthfulness of peanuts (Ronald Pegg, PhD, of the University of Georgia and Kathy McManus, MS, RD, LDN, from Brigham & Women’s Hospital here in Boston); Mark Manary, MD, a pediatrician from St Louis who has spent the last 20 years in Mali, helping to reduce hunger and disease through The Peanut Butter Project; and Bill Briwa, one of the lead teaching chefs at Greystone, who taught us all sorts of culinary tricks and demoed a number of peanut recipes.

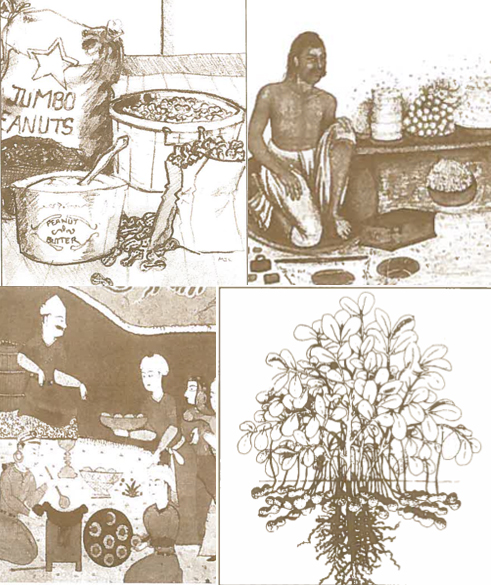

Being from Oldways, my job was to talk about the peanut’s global culinary appeal, because truly, it is one of the few foods featured in cuisines around the world. We’ve collaborated with The Peanut Institute — particularly surrounding the science of healthy moderate fats — since the early days of the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid in the 1990s.

Immediately before our International Conference on the Diets of Asia in 1995, Oldways organized a 2-day symposium on nuts and legumes. Then we created a monograph on Peanuts and Health from the Symposium. In this monograph, food writer Anya von Bremzen wrote as part of her keynote address, “Of all the New World edible discoveries only the chile, perhaps, has enjoyed such stunning success in its travels around the globe.”

It is difficult to overstate the role of peanuts in healthy traditional world cuisine. One way to gauge this is to thumb through the index of cookbooks written by well-traveled and respected authors. Satays, sauces, cookies, stir-fries with peanuts, sweets and confections, salads and greens mixed with peanuts – the list of peanut dishes is a long one, rich with history.

But it is health that drove the peanut to be a building block of healthy, traditional diets. Throughout centuries, legumes have been an essential component of traditional diets. Whether in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Far Eastern cultures, or in Central or South America, humans have subsisted for millenniums on diets based upon one or several legumes.

While peanuts are botanically legumes, from a culinary perspective, they are used like a nut. This connection between the two is close. Legumes and nuts share very important characteristics. The first one is the ability to be stored without refrigeration. Therefore, they can be consumed after some time, even years after harvesting. They share another property in that they both contain a good amount of protein – something they also have in common with animal products Since we’re talking about the old ways, let’s go back to the beginning – to discover the roots of the peanut’s starring role.

Most everyone thinks the peanut originated in Africa, because of the peanut’s connection to the slave trade. The truth is that it’s a New World food, South American, most likely from Bolivia or Peru.

Peanuts were brought to Africa by Portuguese slave traders. and their popularity spread slowly. Culinary historian Jessica Harris reports in her book, The Africa Cookbook, that “The Mandinka of western African still remember this and refer to the legume as tiga, a diminutive of the Portuguese word manteiga, meaning butter” since the oil of the peanut was used for cooking.

The Africans recognized the incredible nutritional potential of this new food (26% protein by weight), plus the plant enriched the soil with nitrogen. The peanut became the plant with the highest protein yield per acre. Besides being a major source of nutrition, the tastes of peanuts became central to West African cooking.

Peanuts could be eaten toasted as a nut or consumed raw like other legumes. Raw peanuts were boiled much like dried peas and served as a side dish. In Ghana and Nigeria peanuts were cooked together with dried corn and made into flour and peanut butter.

The peanut traveled back to Brazil and was re-introduced to Northeastern Brazil by African slaves. Often cooked with okra, it was made into stews — similar to those in the African Heritage Diet.

Similarly, the peanut traveled to the US with African slaves who cultivated and cooked with it in the plantations of the south. From the time of the Civil War it spread throughout America. Then a scientist at Tuskegee Institute – George Washington Carver – became a passionate advocate of the peanut, producing a peanut cookbook with 105 ways of preparing peanuts for human consumption.

How did the peanut travel to the East? Anya von Bremzen says the peanut is first mentioned in China as early as 1530, only a little bit after the discovery of the Americas. It was the Spanish and Portuguese again who brought the peanut east – they were spice traders and missionaries. The Spanish took it to the Philippines and the Portuguese to India and Macau, from where it traveled throughout China via the returning China traders. The peanut was widely accepted – the Chinese already knew how to use legumes and nuts. They made sauces and used the peanuts oils.

And with the history of the peanut’s global role in mind, Chef Bill Briwa at Greystone introduced us to spectacular dishes featuring peanuts from around the world. Luckily for all of us, we got to cook at the CIA. We were divided into four groups — North American, Latin American, Asian and Mediterranean — and produced four dishes per group for our lunch. With 16 dishes to try, it was hard to pick a favorite, although I went back twice for Chile-Peanut Crusted Scallops with Jicama Slaw and today I am able to share the recipe with all of you.

Chile-Peanut Crusted Scallops with Jicama Slaw

Ingredients:

Chile-peanut crust

½ cup peanut flour

1 teaspoon Chile de arbol, finely ground

1-teaspoon kosher salt

¼ teaspoon cumin, ground

3 tablespoons peanuts, toasted, ground for garnish

Scallops

12 fresh scallops

3 tablespoons peanut oil

4 skewers

oil, for grill

Jicama Slaw (recipe below)

Peanuts, toasted, for garnish as needed

Directions:

For the chili-peanut crust: Combine the peanut flour, chile de arbol powder, salt, and cumin in a small bowl and mix to combine. In a small sauté pan, toast the mixture over medium-low heat until it just starts to color and the aroma of the peanuts begins to fill the room; set aside and cool.

For the scallops: Rinse the scallops, pat dry, and coat with peanut oil. Rubin with the chile-peanut mixture. Threat 3 scallops on each of the four 6-inch skewers.

Prepat grill to medium-high heat and oil the grill rack. Grill the scallops until cooked through, about 4 =minutes per side. Carefully remove the scallops from the skewers. Serve warm with the jicama slaw and garnish with toasted peanuts.

Serves 4

Recipe courtesy of Bill Briwa, Culinary Institute of America at Greystone for The Peanut Institute

Jicama Slaw

Ingredients:

2 Jicama, medium, peeled, julienned

1 Napa cabbage, cored, finely shredded

3 carrots, peeled, shredded

½ cup lime juice

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

2 table spoons ancho chile powder

2 tablespoons honey

½ cup peanut oil

Salt and ground black pepper, to taste

1 cup cilantro leaves, finely chopped

Directions:

Place the jicama, cabbage and carrots in a large bowl.

Whisk together the lime juice, vinegar, ancho chile powder, honey, and peanut oil in a medium bowl. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

Pour the dressing over the jicama mixture and toss to cat well. Fold in the cilantro and let stand at room temperature for 15 minutes before serving.

Serves 4

Recipe courtesy of Julie Sahni for The Culinary Institute of America at Greystone

Add a Comment