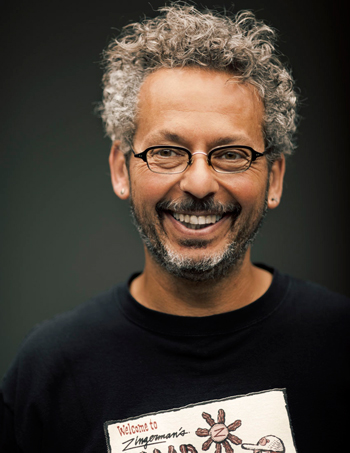

Ari Weinzweig Remembers an Old Friend and Their Cheesemaking Travels

One of the great things about Oldways is the way in which it has allowed so many of us in the food world to connect with other cultures and each other on a regular basis. Sometimes those connections were bold bringing us to areas that we’d never been to, teaching us about foodways that were completely unfamiliar to us. At other times the connections were quieter people or ideas, often already familiar, but that continued to evolve, often quietly, slowly, but ultimately with great meaning and significance for all involved.

The story that follows is one of the latter. I’d been to Crete before, but I was excited to go back and study the traditions of the island in greater depth. As a preface to the trip I made plans to meet up with my friend Greek-born, San Francisco-based cheesemonger and chef, Daphne Zepos for a couple days before the conference opened.

Daphne arranged for us to visit some of the beaten path villages in order to learn the traditional mountain methods of sheepherding and cheesemaking. Our visit was pretty much pure Oldways: we learned, we laughed, we overcame a bit of travel adversity en route, and we all came out better, richer and more knowledgeable for the experience. Friends connect with each other and a very cool, very ancient culture and cuisine and great things emerge from the interaction.

Sadly my friend Daphne passed away this past summer at the far too early age of 53. At her request her friends in the food world have created a scholarship fund in her name. Each year, through the American Cheese Society, the Daphne Zepos Teaching Award helps fund the educational visit of an American cheese educator to Europe. All those who would like to contribute are welcome as we help keep Daphne’s spirit alive.

I’m very sorry that Daphne isn’t here to reread this story now, as you are about to do. She would laugh, remember our experience, add even more detail about the shepherds, what they whispered to her when I wasn’t listening, something small about what they were wearing or the way they looked at us when we arrived. And then she would set to work to help keep the traditional cheesemaking of Crete alive. Which is of course what Oldways is all about.

Greek Mountain Cheese

A Cold Day on a Cretan Mountain

Flora, Fauna And Four Wheel Drive Food Pick Ups

On a Cold Day You Can See Crete

I’d come to Crete for an Oldways conference, expecting an early out from the usual Michigan late-winter blahs. The program packet predicted temperatures in the 70’s: Bring a light jacket or sweater in case it’s cool in the evening.

Cool, I thought, Summer’s coming early for me.

Probably over-packing again, I remember thinking as I slid a sweater and a light jacket into the suitcase.

Crio on Crete

48 hours later I was about halfway up a barren, rocky mountain, smack in the center of Crete, learning about traditional cheesemaking while freezing my behind, and other assorted body parts. How cold was it Well, if Id been properly dressed for a cold winters day at home in Ann Arbor it probably would have felt downright balmy. But standing in the rain, fogalmost a whiteout in some spots and wildly whipping wind in nothing but a t-shirt, thin v-neck sweater and my jean jacket, all I kept thinking was, Why didn’t I bring any gloves My Greek-born, San Francisco-dwelling, friend Daphne, who’d arranged the whole affair, looked down at my hands and laughed: Are your hands always that color, or are you just cold I looked at my angers. Uh, blue No, my hands are not usually blue.

The Greek word for cold is crio. And, let me tell you, it was very crio on Crete.

Of course, the locals lamented, It isn’t usually this cold. Yeah. Small solace that the next week it would probably be about twenty degrees warmer. That was yet to be, and this was, very frigidly, now. In the end though, cold hands and temporarily blue angers were a small price to pay for the chance to observe an ancient art still being practiced in the modern world.

A Country of Contrasts

If your only image of Greece is a land of sun-bleached beaches and white-washed houses on romantically isolated islands, let me say that you’ll and most of modern Greece is quite different from what you might expect. At its heart, modern Greece is a poor country. Ruled for centuries by Ottomans; ravished in modern times by World Wars I and II. While the rest of Europe went into recovery, Greeks were subjected to an additional I’ve years of tragic civil war.

For most of this century, the people of Crete have lived a life tradition-rich, but resource-poor existence. Out of poverty comes ingenuity. Tradition here dictates that nothing goes to waste. Meat is used primarily as a seasoning, added in small quantities to flavor stews, soups and sauces. Mountain herbs became hot beverages. Wild greens, picked from the hillsides, became the basis of Cretan cuisine. In the old days water often became so scarce that the liquid whey left from the cheesemaking which in most places is fed to the animals or discarded was used by mountain villagers to wash themselves.

Life for most 20th century Greeks has not been one for the gods. But through it all the Greeks remained an enormously proud and strong-spirited people.

Greece in general, and Crete in particular, is a country of striking contrasts: brightly colored flowers planted in pastel-painted metal feta (cheese) tins. Orange and lemon trees overhanging old gas stations. Elderly village men sitting outdoors at cafes as they have for centuries, talking, smoking, and drinking, then taking time to answer a call on a cell phone. Televisions in almost every home I saware decorated like old Orthodox icons topped with small, colorful cloths and little collections of what my grandmother used to call tchatchkes/like Mexican retablos.

The Sifakis Family

The cheese we went to see is made by the Sifakis clan: seven brothers and seventy two cousins, was how they describe themselves with obvious pride in their prolic mountain nature. Later someone mentioned, almost as an afterthought, that there were also two sisters. Daphne explained the oversight: this is a patriarchal family. The daughters get only a dowry. The sons share the soil. One brother died years ago in an auto accident. The others are all going strong. There are so many cousins that none of them can name all the others. Not even my wife knows them all, one brother chuckled. (I guess in Greece it must be the womans job to keep track of the familys whereabouts.)

Grigoris Sifakis was our guide to the mountain and the cheesemaking, both physically and spiritually. While he grew up in the village, herding and milking with the rest of the family, he lives with his wife and two sons in the urbanized, eclectic world of HeraklionCretes largest city where he makes his living as a sculptor. An ardent promoter of Cretan tradition, hes clearly the talker in the family, and, equally clearly, he relishes the role. The other members of the family listen, nod encouragement on occasion; and, like most Greeks, smoke plenty of cigarettes.

Daphne pointed out that the Sifakis were divided into two halves by their looks part of the clan is exceptionally good looking. She put Grigoris in the good-looking group: he has thinning, dark hair, brushed straight back, a bushy mustache, and a small bit of a black beard that lends to his intellectual air. The women the older ones at least were clad from head to toe in black; with well-weathered skin; thick angers, and even thicker ankles; and wrinkled, sun-scarred faces. Consistently, I’d say, the women all looked ten years older than their spouses. I mentioned this observation to Daphne. Of course, she red back, The women do all the work so the men can sit around and smoke.

The Alpage/Going Up

Well, it isnt really alpage because these arent the Alps. Technically, its Greek transhumance. In Greek, the term is mitato. Each spring, starting sometime at the end of March, the shepherds in Crete take their sheep and goats up the mountain for summer grazing. The goats like to go up, and apparently they move along with minimal management. The Sifakis swear that the goats will return each year to the same part of the mountain. Even the new generation born in the lowland pastures only a few months earlier will and its way to their traditional goat stomping grounds. The sheep, on the other hand, would rather stay down by the village. Of course they have no say in the matter, so up they go anyway. It takes a day to walk the sheep up the mountain from the villages winter pastures. The animals stay up in the mitato til some time in December, when theyre herded back down to warmer pastures.

Holding on to your herd is no mean feat on Crete. The animals roam seemingly at will; up, down and around the mountains. Some wear leri, traditional bronze Cretan bells, round their necks. The goats get oblong bells, while the sheep wear bells which are wider than they are long. The bells, I was told, are made in seven different sizes, each with its own tone. Like the Swiss herdsman, the Cretans collect bells based on what they believe will make a melodious sound as the herd moves around the mountainsides.

Im not sure exactly what it says about their respective cultures, but its interesting how different the use of bells is on Crete than it is in Switzerland. In the Alps all the cows wear bells, and the biggest bells are bestowed on the best milkers. But on Crete only a few of the animals are so adorned. why I wondered. Only the naughty animals wear the bells, Daphne translated. In a poor country you want to use your resources wisely: the naughtier the animal, the bigger the bell, the easier it is to and them when they run o. One huge-horned buck had an enormously large bell hanging of his neck. I assumed he must particularly willful, exceptionally evil-minded fellow.

To compound the challenges of herd maintenance, Crete has a long, and proud, tradition of animal theft. Back a century or so ago, when the Turks ruled the island, it was a matter of pride to steal sheep from the Ottomans. Making of with part of a Turkish herd was considered an act of bravery. Today the herd has its ears clipped as a mark of ownership. But from the way the Sifakis were talking it was clear that although the Ottomans are long gone, the tradition of sheep-napping has yet to be truly nipped.

Herding

Even the Sifakis, committed as they are to preserving the traditional ways, are yielding to modernity. They do much of their shepherding from four wheel drive vehicles, and use high-powered binoculars to scout for sheep. Yet they still rely on old-style stuck as well. Driving up the mountain, one of the brothers would hop out of the truck now and again, and yell down into the valley: sheep calls are screamed from the mountain tops to and the herds like duck hunters trying to attract their game. Oddly enough, the sheep actually heed the calls. Out of nowhere they come bounding out from behind big rocks and head for the rock-fenced corrals the shepherds build at various spots up and down the mountains.

At one point one of the brothers got out of the jeep and, accompanied by one of the Sifakis experienced sheep dogs, trotted of into the valley. While we drove on ahead, he ran down to roust the sheep. Twenty-five minutes later he showed up, herd in hand, yelling at the sheep and wielding an old fashioned katsouna, the traditional shepherds crook. As the animals approached, the volume rose: a mountain symphony of sheep bells and sheep yells, backed up by the baying and barking of the dogs.

Mountains Southern-Style

These mountains of Crete, are, to my urban eye, the antithesis of those of Switzerland. Swiss mountain pastures are almost like wild golf greens: tidy, terrifically lush, fertile, and filled with tiny wild flowers and fragrant herbs. But in Crete we were on what is, essentially, a mountain of rock. Stones of all sizes are scattered as if a bomb blast had sent debris flying from atop the mountain. There are almost no trees, and green space is spotty. Mostly there’s scrub. Now, mind you, its no ordinary scrub: there’s lots of wild sage, thyme, oregano and other interesting herbs. A few tiny, flowering plants. And a wealth of wickedly prickly, thick, spongy thistle. Working hard to survive creates a hardier, tastier plant, which in turn contributes to exceptionally flavorful milk and cheese.

As in Switzerland, the tops of the mountains are capped with snow seemingly out of character so far south, but, there it was: a generous dusting of white powder all across the top of the range. The snow melts in the summer, bringing liquid sustenance to the fertile valleys down below. Everyone acknowledged how cold it gets up on the mountains. Grigoris told us of, a mountain stream nearby where the water is so cold you cant drink it. As poor as the soil seems, the mountains were actually cultivated in the old days. What could you possibly grow up here on such barren land I asked in surprise. Whatever came,was the response. Mostly wheat and barley.

Milking

Milking sheep is not the route to quick riches. The first part of the herd the brothers milked during our visitabout 70 sheep yielded all of 15 liters of milk! That translates into less than four pounds of vanished cheese for driving up a series of small, rocky roads, standing out in the cold and rain, hand-milking six dozen wild and woolly animals. And remember this is not an optional form of weekend entertainment. It has to be done twice a day!

Daphne and I watched the milking from outside the stone corral. Four brothers, backsides to us, face to the sheep coming out of the enclosure. They roll up their sleeves and get ready to milk, then send the dogs into the corral to keep the herd moving toward the gate. Sheep squeeze out between the stone walls on either side of a rough wood pole stuck in the middle of the opening. They let one sheep at a time start out of the corral, then catch the animals head between their leg, then bend over the animals back and milk it into a bucket that sits submerged in a hole in the ground. Six, eight pulls on each teat and the sheep is shorn of its milk, turned loose to run wild again on the mountain side til tomorrow mornings milking.

The Sifakis own a series of stone huts up on the mountainside where their father and grandfather milked the herds. In the old days the shepherds used to liveand make cheese up on the mountain, coming down for only a day or so at a time. They used to make mattresses by willing cloth with the thistle that grows all over the mountainsides. Up in the corner of the ceiling, theres a hole: the spot where the cheese making kettle was kept. The walls and ceiling are still charred from the oft-lit res. These days, the ascension of four-wheel drive vehicles means that the milk can be brought down to the village every evening, so the brothers no longer bother with sleeping in stone huts. Its still rough up on the mountain, but when they come back down its to clean, dry, nicely decorated, modern homes in the village.

The Village Over There

The Sifakis clan comes from the village of Gergeri (pronounced, Yair-yerrée), which lies on the southern side of the Psiloritis Mountain, due south of Heraklion. If you check out a map of Crete youll see that its center is filled with big brown blotches mountainous areas without villages or paved roads. Gergeri is one of the villages that dot the map as it moves from green to gray to brown at the base of the mountains. The name means, Over There, a reference to the fact that it was far enough up the mountainside that none of the invading Turks ever lived in it. It was just, over there.

Returning to the village from our afternoon on the mountain I finally got a shot at getting warm. Sitting about a foot and a half from the wood stove, I slowly started to shed my few layers of outerwear. A shot glass of raki (Cretan eau de vie), a bowl of unshelled peanuts (not what I’d have thought of as a traditional Greek treat), another raki, then a hot glass of mountain tea, tsai tou vounou. Although the term mountain te is used all over Greece, it refers to different wild herbs in different parts of the country. On Crete it’s faskomilówild sage. Branches of the herb are put into boiling water for a few minutes, then poured into cups.

This is stark living. Neat, clean, tight. Definitely not luxurious.

Dinner with the Family

Cretans are famous for their hospitality, and we were treated both literally and gurativelyto a generous taste of it by the Sifakis. Daphne pointed out though that it was only because she’d met Grigoris a few weeks earlier, earned his trust, passed some unwritten mountain test that meant we had received unwritten Cretan clearance to come into their homes. Once in, we in we were welcomed with incredible warmth and enormous generosity.

After our morning encounter with the elements, we were served a marvelous mountain meal at the home of one of the brothers. We started with makaronia tougámou, a Cretan specialty traditionally served at weddings but now eaten with regularity: a rich goat broth portioned out with a liberal helping of long noodles which had been cooked right in the broth, then topped with a few generous spoonfuls of the family’s aged sheep cheese. Fantastic. Then came some little pitefresh cheese pies fried in olive oil. A platter of pieces of roasted goat, served cold, still on the bone. Then mzithra pitea thick, at, pan-fried bread with fresh cheese mixed into the dough. Bread was traditional Cretean paximadiidried barley rusks sprinkled with water then squeezed dry. We drank local rosé wine. As we ate one extended family member after another stuck their head in to say hello. I couldn’t tell whether these visits were a regular a air or just a chance to check on the American visitors.

Finally, the Cheese

Unlike Northern Europeans, who often make their cheeses only in the morning (mixing the milk of the previous evening with that of the following morning) Cretans make mountain cheese twice a day. After dinner we headed a hundred meters or so down the road to a small, dimly lit, room where the evenings cheesemaking had just begun. Concrete doors and walls, an old propane-red metal kettle in the corner for the cheesemaking; a jumble of cheese-related baskets and assorted accouterments stacked in no particular order around the rest of the room. Of in the corner was a three-foot high entry way to the Sifakis cave, where the cheeses are aged.

We were greeted immediately by the sweet smell of fresh milk being warmed in the kettle. It’s an aroma I’ve smelled in dozens of small dairies around the world. Along the wall, above the kettle, hung a series of wooden tools for cheesemaking. A stick with four prongs on it for cutting the curd. (Mind you, I’m not talking about a polished modern broom handle this was a stick , a crooked branch, cut from a tree.) Next to it, a wood-handled brush for cleaning the kettle; then a scoop with holes in it for moving the curd from the kettle to the molds; and a stack of woven, wooden toupi, the traditional baskets for packing fresh cheese. If I had any doubts about the authenticity of what we were watching, they were set to rest a few days later when I spotted a similar set of tools on display in a museum of traditional Cretan folk life. The only modern components in the process were the propane for propelling the flames, and the store-bought, powdered rennet used to start the separation of curd and whey.

The cheesemaking is almost a social activity. We visited two rooms: in one, the eldest Sifakis brother did the honors. Next door, an elderly neighbor had his hands in the curd. In both cases, the wife was in attendance as well, assisting like a nurse at the operating table. I took a particular interest in the hands of the old man this dark angers were wrinkled and knotted, like old tree branches after a heavy rain. A cheesemakers hands are the same no matter where you go.

The cheesemaking takes only an hour or so. While the herds are large, the small milk yield means that there’s actually very little cheese made each day. The Sifakis produce a mere three wheels a night; three more in the morning. Later in the spring, production peaks at I’ve wheels per batch.

There are two stages to the cheesemaking in the mountains of Crete. First the milk is heated, rennet and starter are added. The resulting curd is cut, salted, stirred and warmed in the kettle. When it’s ready, the cheesemaker scoops it out into six-inch high, woven-wood baskets. He presses down on the wet curd with the back of his hand, knuckles down, gently kneading it like dough, in the process expelling excess whey. The curd is skipped over in the basket and the process is repeated. Because the pressing is strictly done by hand, the aging of the cheeses can be uneven. The curd-filled baskets are then set on a wooden trough to drain.

The first piece of the curd that comes out of the kettle is set on the table for immediate eating. In Cretan dialect it’s called malaka, which, much to the hilarity of our hosts, has another, rather racy, meaning which I’ll leave out of this otherwise innocent food essay. It was delicious fresh: soft, fresh, squeaky white curd with a fresh, mild, milky sheep flavor. Most of the cheeses are set aside to age in the cave for about three months. The Cretans call their cheese Kefalotyri, though it is actually quite different from the mainland cheese of the same name which is exported and widely available. After aging, it has a flavor somewhat akin to a slightly sharper and gutsier pecorino. An additional piece of the curd is cut of with a knife and set aside for finishing a few minutes later.

Whey Cheese

The second stage is the making of mzithra, the whey cheese, a Cretan cousin to ricotta. The liquid left in the kettle after the curd has been removed is heated and stirred. A bit of goat’s milk, and additional salt, are added to the whey. While the whey is being heated the reserved curd from the first part of the making is immersed in the hot liquid and worked like mozzarella. The resulting cheese, known as tsivila, is highly-prized. They lust after this cheese melted with eggs for breakfast, Daphne translated.

As the temperature rises, the solids in the whey begin to form up. Soon, they’re scooped from the kettle like they’re curdly cousins, gently placed into baskets to drain. Much of this mzithra is eaten fresh, with honey, or alternatively, with sugar and cinnamon. A good deal of it is used in cooking, like in the pite we’d been served at dinner an hour or so earlier. The rest is set aside to age.

In Babylon they had hanging gardens. On Crete they have hanging aging shelves. They suspend wooden boards with the effective equivalent of coat hangers, outdoors of the sides of the houses, and under the eaves. The thin wire supports give the cheese a safe resting place: it keeps animals and walking critters/insects from getting at it. The whey cheeses age for about three months.

End of an Era

Traditional shepherding and cheesemaking is dying on Crete; an ancient craft, it’s also a very, very hard life. Never glamorous, often onerous. Over the last fifteen years or so tourism and agricultural successes have brought a better life to Crete. And the Sifakis aren’t suffering. I can’t say whether it’s the hardest or not what I can say is that herding sheep and making cheese in the mountains of Crete isn’t easy. The Sifakis with their commitment to Crete’s traditions won my deepest respect. They stick to their roots when most others would have given up long ago. Yet, as hard as many aspects of their life may be, theres also an enviable joy, an appreciation for life that I admire.

As I traveled back to Ann Arbor, through too many hours of airports and airplanes, I gave a good deal of thought about whether I ought to include the story of the Sifakis and their cheese in my book. It’s unlikely you’ll ever get to try to the Sifakis cheese first hand. They make very little cheese, and much of it is eaten by the family. The wheels that do leave the village are sold of in Heraklion an hour away.

But although you may never taste the cheese itself, it seemed a shame not to share what I experienced on Mt. Psiloritis; to at least give a mental taste of Crete’s mountains, its cheesemakers and its unique cheeses. When you think of Greece, of Greek cuisine, or of mountain cheese, I hope you’ll imagine the brothers bringing down the sheep’s milk, making cheese the old-fashioned way, doing their best to preserve Crete’s mountain cheese traditions with pride and integrity. This has to be the hardest life, Grigoris told us with grave seriousness. iI know in my heart, it’s the hardest.

-Ari Weinzweig

Leave a comment