For many, spring signifies rebirth and renewal. For me, it also conjures up some really vivid family meals and holiday celebrations. While I’ve never been particularly enthused by the winter holiday season (perhaps it is the summer baby in me that craves sun and green things), I’d liken my feelings to this time of year to other people’s yuletide joy.

This is the season that makes me reminisce most about my dad’s cooking: always some form of meat, gravy, and potatoes, along with dressing (he was not a light hand with the starch!) paired with tender spring beans and/or collards. And I think of my mom, as she prepared Passover staples: matzo ball soup, usually my favorite brisket with caramelized onions, and a matzo dessert kugel laced with blackberry jam, washed down with grape juice or impossibly sweet blackberry Manischewitz (aka a wine only a kid could love). Our much-dog-eared haggadah (filled with prayers, queries, commentary, and song for the Passover holiday) lived underneath our massive and ancient microwave, only to be unearthed once a year for our very casual seder dinners.

The liberation theme of Passover, a holiday that commemorates the Israelites exodus from Egypt, resonates on both sides of my family. Africans and Jews have traveled similar trajectories at times as strangers and outsiders, people of far-reaching diasporas, not always equal under the eyes of the law and their countrymen.

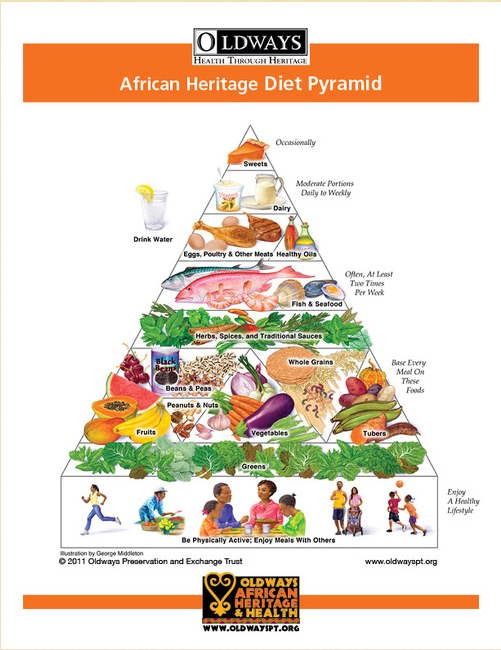

In considering ways to honor both sides of my lineage and to share my table with all of my people, the Passover seder plate, with its full palette of colors and its variety of tastes (salty, bitter, sweet), comes to mind. This plate is the centerpiece of the table during the first two nights of Passover. It is referenced during readings from the haggadah, and it contains important symbols of the Israelites time in Egypt. Food historian and fellow African American Jew Michael Twitty recreated his own version of the plate based on the foods consumed by his African ancestors. But as it turns out, the seder plate is very grounded in the Oldways African Heritage Diet Pyramid. I’ve explained the elements below and how they correspond with the Diet Pyramid.

- Zero’a: a roasted shank bone of lamb, or a roasted chicken bone. This signifies the sacrificial lamb offered to the Temple. Moderate portions daily to weekly of lamb and chicken are included in the African Heritage Diet Pyramid, but if you’d like to keep things meatless, you could substitute a roasted beet.

- Baytzah: a roasted, hard-boiled egg that is offered as part of the sacrifice along with the meat. It also represents the human life cycle. As with the lean meats above, eggs are included in moderation on the Pyramid. For vegans, a roasted avocado pit would do the trick.

- Maror: These are the so-called bitter herbs that signify the bitterness of enslavement. Horseradish, romaine lettuce, and endive are all popularly used (You may be thinking that two of these aren’t exactly bitter, and NONE are herbs, but that is a story in itself). Although they may not be on the official list of bitter herbs, bitter or peppery greens from the base of the Heritage Diet Pyramid, such as dandelion, mustard greens, or watercress, make good substitutes.

- Karpas: This is a fresh spring vegetable, such as celery or potatoes; or confusingly, an herb like parsley (but not a bitter one). It is dipped in salt water in order to stand in as the tears of the enslaved Israelites. The African Heritage Diet Pyramid again offers some alternatives: asparagus and peas are the springiest of vegetables, and sweet potato is a good stand-in for potato. Cilantro could also substitute for parsley.

- Charoseth: This sweet mixture of nuts, spices, wine, and dried or fresh fruits (apples are common in the U.S.) represents the mortar Israelites used in their construction for the Egyptians. It is delicious! This one can be quite fun to play around with, so try it with some combination of eggs and/or dates, dried papaya or mango, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, coconut, walnuts or peanuts, and honey. Here’s some great inspiration including a Ugandan recipe for charoseth.

Another easy way for me to incorporate African heritage foods into my Passover is through tzimmes, a traditional vegetable stew (meaning big fuss in Yiddish). It is a staple of the Passover table that is not unlike the North African tagine, usually served with meat such as brisket. But it doesn’t have to be! This dish, after all, is a perfect vehicle for the beautiful tubers, fruits, and vegetables you’ll and in Lessons 5 and 6 of the A Taste of African Heritage curriculum. My version is less traditional because I’ve chosen to roast my vegetables instead, giving them more texture, and I’ve also added some intrigue with the slightly sweet and aromatic North African spice blend, ras el hanout. I squeeze just a bit of fresh orange juice over the roasted medley before serving.

RECIPE: Roasted Tzimmes with Ras El Hanout

Yield: Serves 6

Total time: 35 minutes

1 2 Tablespoons extra virgin olive oil (or coconut oil)

1 Tablespoon honey

1 ½ teaspoons ras el hanout spice blend

1 teaspoon Kosher salt

2 medium sweet potatoes, halved, and sliced into ¼-inch thick half moons

2 medium carrots, peeled, and sliced into ¼-inch thick coins

1 cup prunes, sliced in half

Peel from one orange, in large strips (reserving the juice of the orange for later)

- Preheat the oven to 425 °F. In a small bowl, whisk the oil, honey, ras el hanout, and salt together. In a medium bowl, toss the sweet potatoes, carrots, prunes, and orange peel with the oil mixture until they are thoroughly coated. If you have the time, allow the vegetables to sit for 20 minutes to absorb all the flavors.

- Pour the vegetables onto a sheet pan, and distribute so that that they are spread into a thin layer.

- Roast the vegetables for 15 minutes undisturbed.

- Check the vegetables, and use a spatula to zip them over, making sure that they are still spread into a thin layer. Rotate the sheet pan and roast for another 5 to 10 minutes, or until fork tender.

- Remove the orange peel. In a large bowl, combine the vegetables with the orange juice before serving.

Note: using some cosmic purple and yellow carrots make an attractive presentation, but note that they may take longer to roast than orange carrots. You can also add chopped roasted nuts like almonds or pecans for additional texture.

Of course, not everything on the African Heritage Diet Pyramid lends itself so easily to Passover celebration. Consequently, no matter how you celebrate, you’ll have to forgo some significant African heritage foods during the 8 days of Passover if observing the rules. The biggest culinary prohibition during Passover is that a Jew is not to consume leavened bread in commemoration of the Israelites haste in feeing Egypt. This sounds simple, but it isnt. Wheat, rye, barley, oats, and spelt that have not been completely cooked within 18 minutes after coming into contact with water are considered of limits. After this point, the grains are considered risen. Additionally, the rules become even more complicated depending on your Jewish origins. For example, Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews) do not eat fermented foods like yogurt; many Ashkenazi (central or Eastern European Jews) do not eat rice, corn, millet, beans, lentils or peas, while Sephardic and Mizrahi (Jews from the Iberian peninsula and the Middle East) do not have these restrictions. The good news, however, is that there is still a wealth of leafy greens, fruits, vegetables, and tubers in the African heritage diet from which to choose when designing your Passover menu. And for those worried about their whole grain consumption during the month, supergrain quinoa is there to save the dayt he gluten-free seed that is prepared like a grain has been approved as kosher for Passover. Enjoy the tzimmes above with some quinoa; together they make a well-rounded, African heritage Passover dish!

Johnisha Levi, Program Coordinator, African Heritage & Health